We’ve written a lot about the death of the recorded music business, but in a keynote address to a music industry conference a couple weeks ago Topspin CEO Ian Rogers sketches out a different future. Rogers, the former head of Yahoo Music, correctly points out, as others have before him, that it is not the music industry that is dying. It is the CD business.

And as far as the CD business going the way of the dodo, with sales of physical CDs declining and the growth of digital sales not making up the difference, his response is:

I don’t care.

The lamenting we read in the press is not the story of the new music business. Continuing to talk about the health of the music industry on these terms is as if we’d all been crying about the dying cassette business in 1995. The difference is that when we moved from cassette to CD the winners were the same (big companies who owned access to cash, distribution, and marketing) and the definition of winning was the same (more units sold for these big companies).

As I’ve been saying for years, the physics of the media space have changed and you shouldn’t expect the winners or even the definition of winning to stay constant, so simply looking at how iTunes replaces CDs doesn’t tell the entire story.

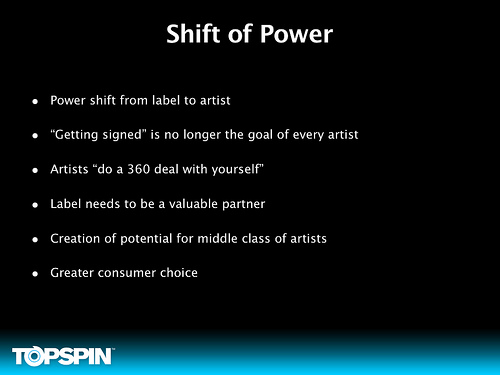

I see news about the health of the music industry as defined by the stock price of WMG or quarterly earnings of UMG, Sony, and EMI every day. What I don’t see, apart from a few articles on Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails, is an update on how the world is changing from the artist point of view. But I tell you, when I talk to managers and artists they feel it, they feel an ability to take their careers into their own hands, to redefine what success means for them, and that is the emergence of the new music business.

He argues that what will replace the current hits-driven music industry is a broader middle class of artists that can support themselves using the Web to promote their music, shows, and merchandise. Rogers illustrates his argument with two examples of artists who distribute their music through Topspin and are making more money than they would under the traditional system.

The first example is David Byrne and Brian Eno’s new album Everything That Happens Will Happen Today. By distributing digitally and keeping most of the profits themselves, the gross revenues of the album matched what they could have expected to get as an advance from a music label within the first 50 days. The second example is a lesser-known artist in his twenties, Joe Purdy, who has sold 650,000 tracks on iTunes and was able to buy a house from the proceeds.

Rogers concludes:

Digital sales don’t make up for physical? From the artist perspective they certainly can, and quickly. David and Brian keep the majority of the profits, and (via Topspin at least) are paid within sixty days of the fan purchasing (no wait for recoupment and complex royalty accounting). When your costs are low your royalty rate high and your channel direct, the marginal profitability from the artist perspective can be far different than in the old model, to be sure.

And where the mass-marketed approach was low-margin from the artist perspective, the target-marketed approach can be much higher margin (which is how Joe Purdy buys a house on his iTunes sales). Topspin believes there is an entire middle class of artists for whom the system hasn’t worked in the past who will be empowered by this new model.

Again, there are only two players in the music business that matter at the end of the day: the artists and the fans. The rest of us . . . either add value today with a compelling service or we die. And I’m perfectly happy with that.

Rogers is right. The music industry needs a bigger middle class of artists. It also needs more people like Rogers trying to create that middle class.