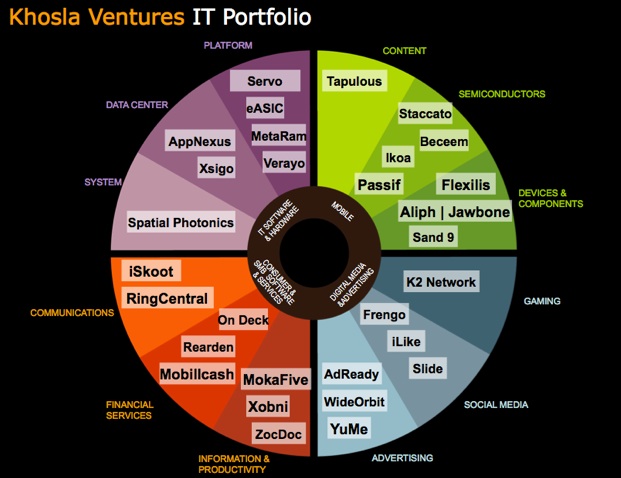

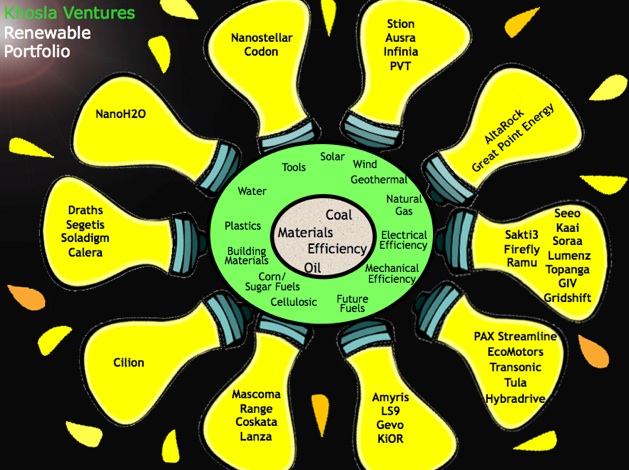

In venture capital, Vinod Khosla likes to go his own way, which is why he’s been so successful. He was the founding CEO of Sun Microsystems, and then moved to venture capital and became a star partner at Kleiner Perkins, where he backed Juniper Networks, Cerent (sold to Cisco for $7 billion) and NexGen (sold to AMD and formed the basis for its challenge to Intel). About five years ago, after becoming a billionaire, he left Kleiner and started Khosla Ventures to invest his own money. He was mostly drawn to clean tech at a time before it was popular, but still kept his hand in Web and other tech startups (Aliph|Jawbone, iSkoot, RingCentral, Tapulous, iLike, Slide, Xobni). Khosla Ventures already has more than 50 companies in its portfolio (see slides below).

Earlier this month, Khosla raised $1.1 billion for two new funds, taking money from outside investors for the first time. I spoke with Khosla on the phone about his new fund, his approach to investing, clean tech and more. He compares Web startups to water startups, dismisses entrepreneurs who think about exits before building value, and contends that cleantech companies can command as high margins as hardware or software companies. “It’s a business strategy decision,” he explains.”

In the interview, Khosla talks about his investments in Aliph, RingCentral, eASIC, iSkoot, and Xobni. In terms of what he’s looking for, he declares “we love material science.” And in his seed fund, in particular, he says, “We’re not looking for completeness in things. We’re not looking for business plans. We are not looking for meeting every fiduciary requirement of an investor. We are looking for great technical ideas and great technologists.”

The 25-minute interview and full transcript are below. I’ve bolded parts for emphasis.

Vinod Khosla TechCrunch Interview: Play Now | Play in Popup | Download

Vinod Khosla TechCrunch Interview: Play Now | Play in Popup | Download

//

Interview Transcript

Mr. SCHONFELD: Well thanks for taking the time to speak to me. You just recently raised a pretty large fund or actually a couple of funds, right, $1.1 billion for two new funds. And I believe this is the first time you really took outside money. Can you talk a little bit about that whole fund-raising process and why you decided to reach to outside investors?

Mr. KHOSLA: I think my general feeling is the scale of the opportunity we see is pretty large. You know, when I started doing things on my own, I was figuring – remember it was a very nascent market. And there was a lot that was unknown about the renewable marketplace in 2004, early 2003 when I was planning on it. The world does change for the better. Much larger opportunity set and it probably requires, you know – there’s more opportunity than I would have thought five years ago.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Right. Now, you have been really focusing on this area specifically for five years. While still, you’re still making an investment in more traditional web companies and the type of technology companies you’ve been investing in for years. But can you just tell me a little about the difference in the dynamics between the companies that are renewable energy companies versus the companies that our readers probably are more familiar with, web companies and hardware and even chip companies.

Mr. KHOSLA: Yeah, still…

Mr. SCHONFELD: There seems to be a disconnect, even in the Valley, between the cultures of these two types of tech companies.

Mr. KHOSLA: You know, I find that a pretty narrow view on behalf of people who sort of repeat that, I’ll call it a platitude for now. In the following sense, if you look at a venture firm like Kleiner Perkins and look at their portfolio, I would guess that 20 percent of the portfolio —and this is before renewables—ends up in things that are purely capital-intensive like biotech. 20 percent ends up in really capital-intensive stuff like biotech. 20 percent ends up in capital-light things like a Web start-up, let’s say, taking less than $30 million. So, 20 percent will take less than 30, 20 percent will take more than 300. And then the remaining 60 percent ends up in the middle taking, oh, you know, the bulk of the portfolio in venture takes between $30 million and $75 million or a hundred million. I think the profile in renewables will look exactly the same. And so, if you’re a broad-based venture firm and you do biotech and you do some of the capital-intensive projects, your renewable portfolio will not look that different.

Not everything in the world is building power plants or build biofuel facilities. There are plenty of things that are in the middle.

So if you’re doing LED lighting, it is just like a chip start-up. If you’re doing a new air-conditioner, it’s like a small equipment start-up, or telecom gear start-up. If you’re doing water, it’s like a Web start-up, at least the ones we’ve done.

Mr. SCHONFELD: How is a water startup like a Web company?

Mr. KHOSLA: Well, for 15, 20 million dollars, they’ll have products in the marketplace and be able to be cash flow positive. Less than $25 million, I would guess, because they’re making membranes. Then you make a membrane, they put it into existing systems. Now, they could have a capital-intensive model and build a desalination plant but they’re not going to. They’re going to build a membrane that goes into existing desalination plants. And so, it’s a very simple model and in all those – in almost all these cases that opportunity exists. Even in the extensive biofuels area, where you’d think it’d be very capital-intensive, you know, it’s easy to cut deals like LS9 announced one with Proctor & Gamble. That’s publicly announced. You can look that up, and make sure it is capital-light. There are companies that are pursuing licensing strategies that are also relatively capital-light.

MR. SCHONFELD: Already you have what, about 50 companies in your Khosla Ventures portfolio, somewhere around there? MR. KHOSLA: More than that. I don’t know the exact count but yes, more. Well above 50.

MR. SCHONFELD: So the new fund will be used for follow-on investments to the existing portfolio as well as new ventures or is it – or the existing portfolio is already taken care of with the capital allocated to the previous funds? MR. KHOSLA: Well, both of the funds will be new investments. But there are provisions for existing portfolio companies to get in, you know, we’re not going into the details but the bulk of the funds will be new investments.

MR. SCHONFELD: And do you see going forward the mix being pretty much the same? It seems like it’s two thirds clean tech and one third more traditional tech. MR. KHOSLA: Yeah. We do expect the mix in the future to look similar to the mix we’ve had in the past.

MR. SCHONFELD: Let’s take both of these techs one at a time. So, the Clean Tech companies are – are these located all over the place? Are these Silicon Valley companies and what’s your criteria for investing in these companies? I mean, at first glance a lot of these companies seem like material science companies or companies that other investors maybe wouldn’t even look at or would pass on because it’s not – it’s not a familiar model to them, right? So, you’ve invested in a lot of technology companies. Obviously, the problems they’re trying to address are large, but in terms of the actual business model and economic models of these companies, where’s the leverage?

MR. KHOSLA: Well, you know, first because it’s a diverse area and there’s no one business model. There will be a range of business models that will be used and will make sense and just like any other tech start-up, these companies are run by entrepreneurs who are pretty damned adaptive. You know, they’ll move pretty quick and adapt to whatever the environment says.

MR. KHOSLA: If the market changes, the money is available or the money is tight, they adapt to that. These things entrepreneurs do all the time. You saw that in the dot-com thing. There were people who could use a hundred million in the dot-com, and people who could adapt and go back to running on a million dollars a year. We saw that in dot-com companies and I think the same is going to be true in this space. And because the space is so large you’ll see a lot of diversity in the range of business models. I forgot the first part of your question.

MR. SCHONFELD: I can rephrase it. What are you looking for when you’re going to make investments in this area, what are the key…

Mr. KHOSLA: To your question, we love material science. We love serious technology innovations and there is a strong bias towards large technology innovations that are sort of disruptive to the current market. And that is very much a charter of what we are doing and we don’t mind larger technology risks especially in the smaller seed fund, which is really geared towards science experiments, which other people generally, as you say, won’t do.

The main fund will look like any venture fund and we’ll invest like any other. We’ll do seed, A and B and C investments. And there the risks probably will be a little less of the speculative stuff the seed fund might do. And I agree with you, there will be fewer people in the domain of the seed fund but the seed fund will do things that take a million dollars here, our $2 million there to roll out a really radical technology idea. And then it becomes a regular business plan.

In that stage, in the seed fund, we’re not looking for completeness in things. We’re not looking for business plans. We are not looking for meeting every fiduciary requirement of an investor. We are looking for great technical ideas and great technologists and yes, lots of PhDs in hard-core science disciplines.

Or just wild ideas that sort of have huge upside potential and sometimes may not need a radical technology breakthrough. So Xobni, which we did in e-mail , is an example of something that would be—in IT that fits into the seed fund because it’s a wild idea to do e-mail in this day and age. It has gotten great traction. So, that’s what we are looking for in the seed fund. In the main fund, we look for more complete management teams and more complete technology.

Mr. SCHONFELD: But for Xobni, that seems at first like the opposite of what you’d be looking for because a lot of people might think that e-mail is done although obviously, it has a lot of problems.

Mr. KHOSLA: Well, in fact I would say most people wouldn’t invest in e-mail because they think e-mail is done. In that case, it was an idea that we thought compelling and without going into the details, users have adopted it and used it enough to prove to us that it is compelling. And so all I’m saying is, we will do non-technology IT stuff in the seed area. We’ve just done another seed that I won’t mention but it’s not renewable but green, it’s just a great idea in a completely wild space that most VCs wouldn’t even think of touching. But it’s a regular technology start-up. And hey, great, so we are open minded on what we are looking for. On the green side, generally it should focus on the technology, technologist, a breakthrough innovation, not just a minor iteration.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Looking at your portfolio, overall which of the companies are the most mature? Have you had any, have there been any exits from the portfolios so far or –

Mr. KHOSLA: You know, we’ve had some – we’ve had a couple of sales and I don’t know which ones we’ve talked about publicly. They’ve been OK, good returns. So, you know, on average sort of a few times our money. Nothing I’d call a home run today but in terms of maturity, obviously, Aliph or Jawbone is a pretty exciting start-up for us. You know, a couple of, sort of nine digit revenues and cash flow positive and all the things you’d look for in a mature company. And you know, and so, eASIC is doing pretty well in semiconductors, we’re happy with that. Let’s see, iSkoot is doing really well in the mobile space. I’m trying to pick different areas.

You’ take something like RingCentral. It doesn’t need any more money or financing, it is relatively mature recurring revenue business – not really worried but you know, we could sell it tomorrow. We have not been in a rush to sell it. We don’t care about exits as much. We care about building fundamental value. So, in that sense we are a little bit different than other investors. Our focus is not on exit. In fact if you talk to any of my entrepreneurs, I’m generally saying don’t sell the company when other investors want to sell. I’d much rather focus on building long-term value in building companies rather than worrying about exists.

In fact, here is the thing, if a business plan talks about exits in the first two or three pages, I throw it out of the basket because I think, culturally it’s the wrong kind of entrepreneur for us. I literally if they talk, or mention exits in the first, say, in the executive summary or the first three pages of a business plan, it’s two strikes against them right there because I’m not interested in people where exit is top of mind. We care about building companies and building values. And that’s sort of the kind of culture we’re trying to do at Khosla Ventures.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Right, so, what advice would you have for entrepreneurs who you know are looking at different options? I mean, when is the right time to sell and when is the right time to keep going?

Mr. KHOSLA: You know, we could sell Aliph today. We could keep the cash flow positive company going. I’d rather take it towards an IPO. RingCentral is cash flow positive, going, you know, over a 100,000 small businesses as customers. We could sell it today but I still think, there’s time to generate value. It depends on what’s going on internally. If there’s good growth prospects and more value to be built then you go build that value instead of trying to get an exit. Wide Orbit is cash flow breakeven and sort of mature. You’d call it a mature company by venture standards, we’re not interested in, you know, getting out. Now having said that, if somebody comes with a great offer, we’ll always look at it. You know, we’re not opposed to exits. All I’m saying is it’s not the first thing we worry about. We worry about building value and building companies.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Right. And so what should entrepreneurs take from the fact that you were able to raise this $1.1 billion fund which I think is – it’s two funds but it was a sort of a single raise, right? Which I think is the biggest in several years. Is that just because you’re Vinod Khosla or do you see something – you see some –

Mr. KHOSLA: You know, I think the message is there are plenty of me-too two investors and there’s good investors around and money from – new money for that kind of thing is tight. But if you’re trying to do something different like we are, then investors, limited partners are willing to put up the money for it. I mean, and there’s definitely, we’re very active with new investors. We’re looking for ventures and our LPs just want us to take the risk for a file I just talked to you about. And there is appetite for risk.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Do you think that we’re going to be seeing more money flowing into venture capital? There’s been a big debate as whether there’s been a reset or not, you know, for investments going to venture capital and you know, just the whole financial crisis and how that impacted limited partners and how big institutions, you know, are rethinking their allocation to venture as an asset class. Is this an anomaly or –

Mr. KHOSLA: You know, my bet is big institutions will continue investing in venture capital but they’ll be more selective. But I don’t think, you know, frankly, we could have raised a lot more money if we wanted to if we had the people to put it to work. So I do think big institutional investors will continue to fund venture capital, but they will be much more selective and not every venture capital group will get follow-on funding. You know, it’s not too loose in my view and I think that’s going to change, and that’s a good thing.

Mr. SCHONFELD: And what’s your view of the IPO window? Will that ever really open up again or are there fundamental structural phenomena that is keeping it down not just the economy, but you know, everything from Sarbanes-Oxley to –

Mr. KHOSLA: I am pretty sure it will open up again. When is a little hard to predict and that’s why larger funds and deeper pockets are better for both venture funds and for entrepreneurs. I mean, today if I were an entrepreneur, I’d be very careful about only going with people with deep pockets. Because it matters. Now much more than it did before.

Mr. SCHONFELD: So if you’re giving advice to – if I’m an entrepreneur looking for different areas to go into and assuming that I can pull together a team with the required expertise, you know, what’s the counter-intuitive sort of space to go into right now? I would even say Cleantech, there’s a lot of startups out there . . . Mr. KHOSLA: You know, my advice to entrepreneurs is to go into the area of their expertise.

Mr. SCHONFELD: What’s the company that you would invest in in a second, but you haven’t really found it yet? What’s the problem that isn’t being solved by the companies that you’ve looked at that needs solving?

Mr. KHOSLA: Well, for example, storage for electricity is not a problem that has been solved. So, it is not a problem that has been solved.

Mr. SCHONFELD: For portable storage, for large…

Mr. KHOSLA: Well, both portable and stationary storage is not a problem that’s been solved. There’s lots of opportunities in bio materials so you know, in information technology there is, like low power is still a big deal. And so it’s hard to sort of single out areas and I see opportunities and interest, in business trends in almost every area.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Right. So what are your feelings about your first company, Sun Microsystems, being acquired? Mr. KHOSLA: You know, I don’t want to – I think it’s better Oracle acquired it and stayed in the Silicon Valley culture than, say, IBM acquiring it. But frankly, you know, that was a long time ago for me.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Where do these new cleantech companies fall? Are they closer to – do they look more like an industrial company when they mature or do they look closer to, you know, a hardware company or do any of these have software-type margins and how is that possible?

Mr. KHOSLA: Yes, it’s possible. You know, in each case, it’s a business strategy decision. I generally disagree with most of the very high margin opportunities. Why? Because it’s a business strategy tradeoff: the lower the margin you take, the faster you grow.

Yes, a Juniper can do 65% margin, but I tried really hard to convince them to go with 50 percent. Actually, it just increases market penetration faster. And so what are you trying to achieve?

And there are times where . . . take somebody like Infinera. I haven’t been on the board for a couple of years so my data is old. But we had a tradeoff between getting 10% margin on the chassis and 80% margin on the cards, or getting 30, 40, 50 percent margin on the total thing. And one was immediate revenue and margin, and the other was locking in lots of chassis with customers at low margin and then they kept buying line cards from you for ten years. It’s a business strategy question and it worked very well for Infinera. So I think this is a red herring.

Every one of our companies has the opportunity to go after niche markets or a large market. And the larger the market, the more aggressive you have to be.

Mr. SCHONFELD: OK, great.

Mr. KHOSLA: OK.

Mr. SCHONFELD: Thank you for taking the time. I appreciate you taking time on your schedule to talk to us.

Mr. KHOSLA: Great. Thanks a lot.