Just because the Internet makes it possible to offer a near-infinite inventory of goods for sale does not mean that consumers will start wanting more obscure items in any great numbers. That is the conclusion Harvard Business School associate professor Anita Elberse comes to in a recent article in the Harvard Business Review that takes on some of the sacred cows of the Long Tail theory.

Just because the Internet makes it possible to offer a near-infinite inventory of goods for sale does not mean that consumers will start wanting more obscure items in any great numbers. That is the conclusion Harvard Business School associate professor Anita Elberse comes to in a recent article in the Harvard Business Review that takes on some of the sacred cows of the Long Tail theory.

The Long Tail is Wired editor Chris Anderson’s theory (based on an article and resulting book of the same name) that as it becomes easier to distribute a wider variety of items, consumers will venture down the long tail of the distribution curve and find the products that exactly match their interests and idiosyncratic needs. Elberse questions this notion:

Is most of the business in the long tail being generated by a bunch of iconoclasts determined to march to different drummers? The answer is a definite no.

. . . Although no one disputes the lengthening of the tail (clearly, more obscure products are being made available for purchase every day), the tail is likely to be extremely flat and populated by titles that are mostly a diversion for consumers whose appetite for true blockbusters continues to grow. It is therefore highly disputable that much money can be made in the tail.

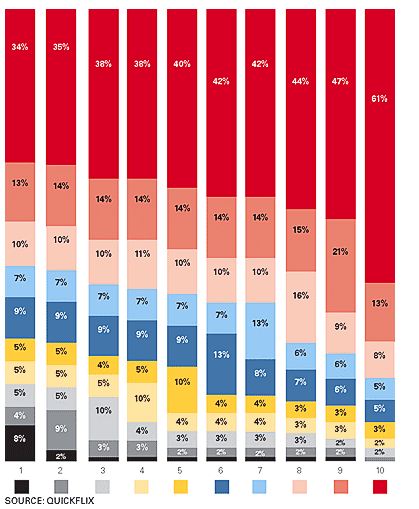

Elberse looks at data from Rhapsody, Quickflix (Australia’s version of Netflix), ans Nielsen for songs and movies. Out of one million tracks she studied on Rhapsody, the top one percent accounted for 32 percent of all plays and the top ten percent accounted for 78 percent of all plays. Similarly, the top one percent of videos on Quickflix accounted for 18 percent of rentals and the top ten percent accounted for 48 percent of rentals. Anderson responds that she defines “head’ and “tail” differently than he would. Even so, he adds, that top one percent of Rhapsody songs is still 10,000 songs, more than what you’d find in a typical record store.

What is more interesting about the study is that Elberse cites evidence that, even given more choice, consumers still flock to the blockbuster products that make up the “head” of the distribution curve. This might be because we are all lemmings or, more likely, that taste in music and movies has a social component. We tend to like a song or movie, in part, because other people like them too. Taste doesn’t form in a vacuum. It is socially reinforced.

Even adventurous consumers who venture into the more obscure realms of inventory tend to buy more hit products than long-tail ones. For instance, QuickFlix customers who rented the most movies from the bottom 10 percent of the distribution curve only did so 8 percent of the time. The largest chunk of their consumption (34 percent) came from the top 10 percent of titles just like everyone else. (In the chart below, the red parts of the bars represent the top ten percent of movie titles, and the black parts represent the bottom ten percent. Each bar, in turn, represents a different set of customers and how their rentals are distributed among each decile of popularity). Elberse concludes:

No matter how I slice and dice the customer base, customers give lower ratings to obscure titles. A balanced picture emerges of the impact of online channels on market demand: Hit products remain dominant, even among consumers who venture deep into the tail. Hit products are also liked better than obscure products. It is a myth that obscure books, films, and songs are treasured. What consumers buy in internet channels is much the same as what they have always bought.

So does this disprove the Long Tail theory? Not exactly. (Lee Gomes’ gleeful grave-digging notwithstanding). All it proves is that blockbusters are more durable than we’d like to think, even in an age of limitless inventory and perfect search.

But to say there is no money in the Long Tail is nonsense. It is just more finely distributed and harder to find. True, there are not many businesses that have figured out how to collect it. Google is one with AdSense and search ads. Each search ad is insignificant in and of itself, but all of those obscure terms add up to billions of dollars.

Is this repeatable in other markets? Elberse herself notes that demand is being pushed down the tail. Even if they can gather up that new demand, Long-Tail businesses may not become the most profitable. The economics have changed. And Google is likely the exception rather than the new rule. But neither can that Long-Tail demand be ignored.

In the end, Elberse presents a false dichotomy. The choice is not head or tail. It’s both.